The year was 1990. I was in Detroit, Michigan working as a resident physician in Internal Medicine. Detroit was dilapidated, its old structures were crumbling, boarded up unkempt houses in neighborhoods once humming with life were now empty, desolated, overgrown with weeds. Brick walls of the old houses, once rock-solid were now fragile and cracked, in some of which parasitic plant lives had found foothold telling the story of once mighty Motor City. A drive through such neighborhoods evoked an unknown anxiety and fear that was only interrupted by sight of an occasional industrial park, equally gloomy, in disrepair, hauntingly desolate, behemoth brick buildings with broken glass windows and ragged pitched roofs still oozing melted snow, as if only kept alive in this state of coma by some unknown force just to remind people of the old industrial glory of Detroit.

Coming from Bangladesh, an overpopulated country of 2000 people per square miles, it was terribly lonely for me not to see any people on the streets and neighborhoods deserted whereas in my home country it was hard to see an inch of empty spot devoid of humans. I was struggling in my conscious and subconscious to reconcile and digest the contrast. Loneliness that I found impossible in Bangladesh, now in Detroit was over abundant and almost overwhelming.

Demand of residency training, both physical and mental vigor that is called for from a young trainee doctor, kept me busy and had distracted me somewhat, perhaps even protected me from the malady of loneliness. Working in a large urban medical school training program I needed to rotate through many different hospitals. Allen Park Veterans Administration Hospital and Medical Center was one such a place.

Allen Park, twenty minute South and West of Detroit was a small working class community of Downriver area. Houses were small but neat, yards were tiny yet tidy. The imposing structure other than nearby shopping mall was the VA Hospital. As I drove the very first day of internship towards this hospital, the first sight of the sprawling red-brick building stuck right next to the freeway, with its multi-floored structure and hundreds of small panes of glass windows on all sides seemed like I was being watched by a giant alien with hundreds of eyes looking out over the plains. The sight was overpowering. As I approached the building close, the billowing cloud of smoke from the smoking veterans on both sides of the entrance outside greeted me with an aura of Burmese Opium Den.

But time is a great healer; distance is the halcyon; work is the opium; my old familiar sights and sounds from the home country of Bangladesh faded gradually, and soon realities and demands of current surroundings took the center stage. Curious part of my brain sprang back into action again, perhaps I subconsciously realized it to be a healthy distraction from the monotonous grueling work of patient care at the VA Hospital. Often in call nights, I would look through the cracks and crannies of the old hospital building noticing the fine color difference of the two buildings put together, the subtle difference of the pinkish bricks, the variation of the poured concrete, the rusted iron rods sticking out as if I was driven by an impulse to find an old skeleton hidden somewhere. There are times at night I would circumnavigate the old buildings as if I were the Columbus on a mission to discover America.

The reason behind as to why the Federal government put this huge hospital in such a place outside the city limits of Detroit was simply another Henry Ford story. In the dark days of Great Depression of the 1930s, the Ford family had donated 38 acres of land to the federal government in Allen Park, MI, as an inducement to set up this VA hospital. The construction work began in 1937. At the end of Second World War as the rank of Midwestern veterans swelled, the hospital was expanded in phases to accommodate the increasing demand. The architects in charge of these renovations never wanted to hide this fact perhaps, because any observant set of eyeballs could easily still tell each additions of the hospital separately.

This VA Hospital was gem of a place to learn for any aspiring medical student. Veterans and the teaching faculties were always easy going compared with elite private hospitals and sophisticated patients therein. Veterans on the other hand, did not have any special demand upon the trainees. VA Patients were always compliant and unabashed at the request of physical examination and as of yet, neither there was the looming threat of malpractice law suits, nor there was any pressure from the administration to discharge anyone early to save the hospital money. In fact the pressure was opposite: to keep patients in the hospital for any reason as long as one can, medical to social. It was not unusual to keep someone for days even weeks in the inpatient hospital service because the veteran had no taxicab fare or bus ride to go home. Apparently each individual VA Hospitals used to get budgeted money allocation according to the census of the hospital. The more patients each hospital had in its rolls the more money were to be allocated. I remember one day, the chief of the hospital came in our morning round and told us to “keep as many patients in hospital as you can so our census goes up since the budget allocation time is coming up”!

Inside the mammoth building it was gloomy dark with old fixtures. The walls were old and bare, as if the building was missing the touch of a woman and truly it was devoid of women at that time. In my whole time of service over several years, I only got to see two or three female veterans in this hospital. The whole hospital building was made for only men by men. The rare female veterans who were to be admitted were kept in one corner of the hospital with only few rooms next to the psychiatric unit, and the make-shift nature of this corner was still obvious.

The Midwestern sun sets early in most of the year except for the few short summer months and inside the VA hospital my heart used to fill with a melancholy as the cloak of darkness descended outside with the setting sun. It was a deep seated ill-defined sorrow, an ache poorly localized, that I could never pinpoint, perhaps the pain of losing my mother whom I saw for the last time I left for US, it was perhaps that I was thousands of miles away from my family, or just perhaps leaving everything behind for USA to fulfill my American dream and the pain and guilt of achieving it! I could really never feel it out in proper shape, I could never bring it out in the open or on the surface, it remained as just an indescribable awareness in the subconscious, a torment that would neither kill nor leave me alone. It remains as a gnawing pain in the belly that can never be localized exactly even till today. Perhaps it is the pain all immigrants feel, leaving things behind for a new life in a new society. Busy chores of the VA residency, from drawing of blood, doing EKGs, and even sometimes emptying the urinals as we had to do due to severe nursing shortage, and the demand of treating patients were the best friends to keep me out of trouble in those days. I sometimes wondered, do many immigrants channel their sorrows in work as I have done? Could that even be one of the reasons for their success in America?

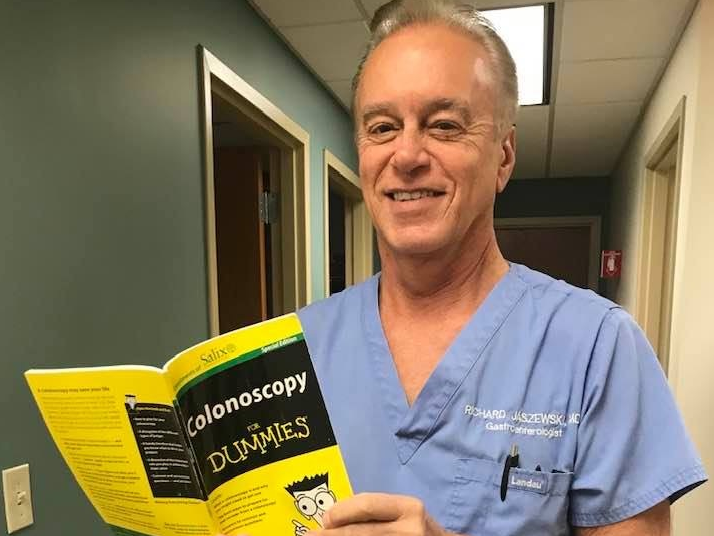

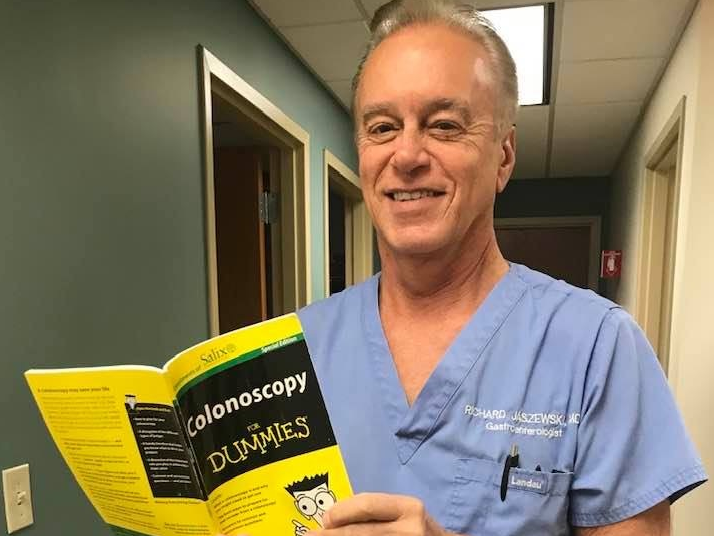

As luck will have it, in such a time and place I met a faculty member from the Division of Gastroenterology, Richard Jaszewski. Rich was a middle aged Northeastern man, nothing distinguished from his look, attire or attitude, a common man of Polish ancestry who was unable to give up his smoking habit in spite of being a doctor and despite seeing all the devastation of smoking especially prevalent among the VA population. His reason for settling in the heart of rust belt was same as mine: medical education and training. His demeanor was calm and, complemented by his soothing voice. From day one as my attending faculty I noticed something special in him. In the morning when we visited each patient with the whole team of doctors, consisting of the attending faculty of the month, the resident, the interns in the team (generally 3-4) and several senior and junior medical students, what is known as the Morning Round, he was very touchy and was exceptionally attentive to the veterans. Often he would sit by the edge of their beds and interact with them face to face at the same eye level. Then we would discuss the management plan among the whole team right on the bedside. Once we were done and about to be leaving for the next patient, he would always say, “Thank you for talking with us”. I’ve even seen when he forgot to tell this phrase to a patient at times, as soon as he remembered he would turn back from the round to tell the patient of this phrase. Every time I heard it, the authenticity and sincerity were self-evident.

From the very first day, I noticed, this phrase of “Thank you for talking with us” had a magical response from the patients. Only a minority of patients retorted to tell something back like “You are welcome or thank you doc”, but majority just looked back and remained silent in surprise but their faces always were glowing with satisfaction and appreciation of the doctor.

It took few days for me to internalize the situation and in due time I took him as my mentor and adopted his phrase, “Thank you for talking with me” at the end of each patient interview. I felt the same magic: feeling of satisfaction, dignity, gratefulness at times mixed with surprise on the part of the patient. From my side I always feel the humility, gratefulness to the patient and the gravitas of the responsibility that I take when someone discloses the very details of their problem and even inner secret and private matters in the process. It is empowerment with humility to me.

My admiration for this mentor subconsciously pulled me in the same direction as of him choosing gastroenterology as choice of career. And ever since it kindled in me a passion for storytelling and story listening. In medicine we call it History. But I am against using this terminology “History”. History subconsciously indicates something objective, a careful dissertation of balanced work after detailed considerations of the pros and cons, a laborious fruit of research on the part of an scholar or an arbiter. But given that a patient is asked to describe their explanation and situation, it is not patient’s job to give an objective analysis, his burden is only to present as how he is feeling. Medical community is only calling for patient’s subjective feeling and description of their own suffering, patient is not asked to be objective about it. So I submit that it is a story that we need to hear and know, not history. I came to realize story listening and storytelling, both are equally important in medicine. Like anything else, life is a two way street. If a doctor cannot tell a patient about his own story when appropriate, patient cannot spontaneously come up with their own story.

I have come to learn that storytelling on the part of the patient is a charity, a giving to the physician, because it enables him to accurately use his knowledge to diagnose and dispense the right management. This is an act of generosity on the part of the patient and it is best reciprocated by a generous “Thank you for speaking with me!”.

Now over two decades have passed since I had appropriated my mentor’s magic phrase for myself in my own professional life. It has always worked for me. It is my secret mantra. And every time I utter this, it reminds me of him and his contribution in my life. The valuable lesson I learnt from him is that a patient’s story is not only a sacred information for me, but it is a gift to a doctor from a patient which we need to recognize and pay back with a thankful note of appropriate gravitas. And a generous “Thank you for speaking with me” from a doctor to a patient at the end of the interview process goes a long way to convey this gravitas. It brings about a trust of the patient to his doctor by message of gratefulness and humility.

Special Note: I started writing this story about two months back and I thought I would get my mentor’s permission to publish his name. Since I graduated from fellowship, I moved to Texas and my mentor moved away from Veterans Administration Medical Center of Detroit to Western Michigan for private practice. Over the years we only spoke few times over phone. I thought best way to get hold of him during business hours will be to visit his practice website. Upon landing his practice website very shockingly I came across his obituary with his ever smiling familiar face. I wish he were alive among us to hear how he taught us and what his legacy is! But such is the world we live in: “For man proposes but God disposes…” I am grateful to his wife for granting me the permission to publish his name in this short memoir, but I am ever grateful to him for being my mentor and for the knowledge he so generously donated for my growth.

I had worked with Dr. Jaszewski for total of six most productive years of my life. I first got to know him in the year of my first year residency also known as internship. After three years of residency in internal medicine, I worked even more closely with him as a gastroenterology fellow, since this was his specialty and he was the Head of local VA Gastroenterology. He knew that I was deeply influenced by him. In fact he was one of my sponsors for this fellowship training that starts after the residency in internal medicine. I am deeply indebted to this man.

Bless you for story telling and being a very passionate doctor.

Thank you for sharing the wisdoms of caring patients it was indeed a very insightful and main learning point was clearly and brilliantly expressed.

Thanks

Dr Ehsanul Karim

Internist, west palm va medical Centre

Wear palm beach florida

Your story about your first experience was very spontaneous and the important magic word you learned from your colleague” thank you for talking with me”. I saw in your Chittagong Medical hospital “ curtesy does not cost money” but unfortunately our Doctors do not care less for curtesy, they want money. Even they don,t spend few minutes with patients. I had bitter experience, I went to a Doctor at Prescribed point in Dhaka once, very highly qualified from America with MD, I had discomfort in my stomach. He gave me 5 medicines. He is not aware I have some idea about the medicines, so I requested him saying “ could you please tell me what is this medicine for? He straight away told me, if you understand better than me you should never come to me. I went out and teared his prescription and just got one medicine which I know. Later I confirmed with Jhumur. Please correct the name Dr. Ehsanul karim not Klarim.

I too had the joy of working with and for this humble physician. Thank you for your story. He was loved and missed by many. Especially his dear wife and family.

Dr. “J” was an extraordinary man. He was kind, caring and empathetic. It was a pleasure to work with him and learn the importance of patient interaction.

I was saddened to hear of his passing. Those of us who knew him will always cherish his memory. Rest peacefully Rich.

It was also my privilege to work with Rich in Allen Park. Gastroenterology was a department I worked very closely with, since I am a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist. My experience with Rich spanned from simple diet instructions to the critical care/Nutrition Support-TPN patients. Rich was always compassionate and humane when it came to patient care. He was also a wonderful teacher and I learned so much from him.

I enjoy reading through an article that will make men and women think.

Also, thank you for permitting me to comment!

Here is my web site; m88

There’s certainly a lot to know about this subject.

I love all the points you made.